In the early 1980s, India and China were often lumped together in conversations about developing nations. Both had massive populations, low per capita incomes, and beleaguered infrastructure. Yet, four decades on, China has emerged as a global manufacturing and tech behemoth, while India remains largely an IT services powerhouse — still dependent on Western innovations it helps support rather than lead.

For many observers, the divergence points to one pivotal difference: vision. China embarked on a road to becoming the “factory of the world,” while India found comfort as the world’s back office. The question now is whether India’s largely service-oriented economy can pivot toward robust, homegrown innovation — or risk being left behind.

Early Similarities, Different Paths

In 1980, India’s population stood at roughly 687.8 million, China’s at 981.2 million — both saddled with slow growth and limited industrial infrastructure, according to data from the World Bank. The per capita gross domestic product of each country at the time hovered under $300 in nominal terms, placing them among the world’s poorest.

But China, under Deng Xiaoping, made the strategic decision to focus on manufacturing and export-led growth. It poured resources into roads, ports, and power plants, offering tax incentives and business-friendly policies that drew in multinational corporations. By the 1990s and early 2000s, its factories were churning out goods for customers worldwide, including those in India itself.

India’s economic liberalization came in 1991. While it ushered in new opportunities, a booming middle class, and rising investments, the primary beneficiaries were service-based industries — chief among them information technology. Companies such as Tata Consultancy Services (TCS), Infosys, and Wipro rose to global prominence by providing outsourced software development, call centers, and tech support.

For India, IT services were a godsend,” said a senior technology executive at Infosys who was not authorized to speak publicly. “They created millions of well-paying jobs. But the question we never asked was: Are we doing anything beyond providing labor?

Indeed, India’s IT exports reached $178 billion in fiscal year 2021–2022, according to the National Association of Software and Services Companies (NASSCOM). That figure underscores an industry integral to India’s economy, but also one deeply tied to Western business cycles.

(Sources: World Bank — Historical Population Data; NASSCOM)

A Service-Driven Nation in a Product-Centric World

Over the past two decades, major American technology companies led global innovation in e-commerce (Amazon), cloud computing (Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure), social media (Facebook, Twitter), and electric vehicles (Tesla). Indian IT giants, meanwhile, mostly specialized in implementation and support.

That India has been happy to remain a service provider is evident in how it has approached new technologies. Most Indian companies have concentrated on contract-based software services for Western clients, rarely investing heavily in research and development for proprietary products.

“When the U.S. sneezes, the Indian tech sector catches a cold,” said one industry analyst in Mumbai. “We have no deep intellectual property in AI or EVs or chip manufacturing that can protect us from the inevitable global ebbs and flows.”

(Source: NASSCOM — Indian IT Industry Report)

Meanwhile, in China…

China was not content to be just the manufacturing hub for the world. Over the last 15 years, it has ramped up spending on research and development, hitting approximately 2.4 percent of its GDP in 2021 (around $445 billion), according to UNESCO Institute for Statistics. In comparison, India’s R&D investment stands at around 0.7 percent of its GDP.

Beyond spending, China aggressively reformed its education system to emphasize science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). It also introduced programs like the “Thousand Talents Plan” to lure top academics from around the globe, including from Ivy League universities in the United States.

China decided it wanted more than just to assemble goods; it wanted to invent and design them,” said Dr. Zhou Li, a professor of economics at Peking University. “The government made it attractive for scientists and researchers to come home or relocate to China.

Today, China has become a powerhouse in cutting-edge technologies — leading the world in electric vehicle sales (approximately 6.9 million in 2022, according to the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers), dominating solar panel production, and publishing more AI-related research papers than any other country, according to a Stanford AI Index report.

(Sources: UNESCO Institute for Statistics, China Association of Automobile Manufacturers, Stanford AI Index Report)

Youth and Unemployment: India’s Demographic Dilemma

India’s median age is around 28, one of the youngest in the world. The country also produces approximately 1.5 million engineering graduates annually. Yet many lack the practical skills necessary for manufacturing or advanced technology jobs. A mismatch persists between what employers need and what academic institutions teach.

Underfunded Public Education

Despite India’s rise as the world’s fifth-largest economy, government spending on education has largely hovered around 3% of GDP — significantly lower than many developed countries and even emerging peers. The result is an underfunded public education system in which schools struggle with inadequate infrastructure, teacher shortages, and outdated curricula.

The irony is that some of India’s brightest minds graduate from a handful of elite public institutions — like the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) — while the majority of public schools languish,” said a professor at a leading IIT who requested anonymity. “The government fails to scale up what works in these top-tier institutions for the rest of the system.

Because public education remains under-resourced, parents who can afford it send their children to private schools, which often boast superior facilities and teaching standards. This has led to a two-tier education system, widening inequality and leaving vast numbers of youth — especially in rural areas — ill-prepared for higher education or the job market.

(Reference: Government Data on Education Expenditure; UNESCO Institute for Statistics)

Missing Apprenticeships and Vocational Training

Beyond basic schooling, India has not significantly expanded apprenticeship or vocational programs that could create a pipeline of skilled blue-collar and mid-level technical workers. While schemes like “Skill India” and “Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana” exist on paper, their reach and effectiveness have been questioned.

This shortfall is often attributed to a lack of coordination between industry and the government, as well as insufficient incentives for private companies to invest in in-house apprenticeship. It also reflects a deeper issue: the political class tends to focus on short-term electoral gains rather than structural reforms that would bear fruit over the longer term.

(Reference: Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship)

Politics Over Policy

Many observers contend that the frequent electoral cycle contributes to a preference for populist measures over genuine systemic change. With India holding some type of election — local, state, or national — almost every year, politicians are often consumed by caste arithmetic, religious polarization, and immediate voter appeasement.

As a result, even flagship government initiatives like “Make in India” and “Digital India” rarely provide robust frameworks for skill development or the modernization of public schooling. Private educational institutions — while generating revenue and prestige — do not solve the systemic challenge of delivering quality education to the broader population.

A Moment of Reckoning

For India’s young, this reality translates into a mismatch between education and employment: large numbers of graduates, but few with the requisite skills for high-demand industries. Employers often cite a lack of job-ready talent, while job seekers struggle to find meaningful work. If India is to truly leverage its demographic dividend, analysts say it will need a decisive pivot toward investing in human capital — starting with public education reform, strong vocational programs, and a political shift away from immediate electoral concerns to long-term national development.

Without a radical reorientation of priorities, the country risks losing its demographic edge. A more robust approach — one that includes upgrading public schools and colleges, allocating higher budgets for teacher training, and scaling apprenticeship programs — could unlock India’s immense potential. But that will require clear-sighted vision and commitment from leaders who understand that nation-building extends far beyond the next election cycle.

Government initiatives such as “Make in India,” announced with much fanfare in 2014, have had mixed results. Foreign direct investment has increased in some sectors, but large-scale factories and manufacturing clusters comparable to China’s Guangdong province remain elusive.

(Source: Government of India — Make in India Initiative)

Indian IT’s Service Mindset: A Recent AI Debate

Nothing illustrates India’s reluctance to step into the product arena more than the current debate around artificial intelligence. Nandan Nilekani, co-founder of Infosys and a widely respected figure in India’s tech ecosystem, recently urged Indian AI startups to avoid building large language models (LLMs) themselves. Instead, he suggested focusing on “practical AI applications,” collecting data, and deploying in a frugal manner.

Around the same time, TCS CEO K. Krithivasan noted that if you look at India’s tech heritage, “we are more of system integrators … we are better off” continuing in that role. These statements, while pragmatic, reveal a preference for incremental service-based work rather than undertaking the risk and expense of building original AI models that could serve as the next wave of technological disruption.

It’s not surprising to see top executives advocating a less capital-intensive approach,” said an Indian AI entrepreneur who asked not to be named. “But the cost of not owning the IP in AI is that you remain dependent on technology from America or China for the next few decades.

The Consequence of Falling Behind

As artificial intelligence rapidly becomes a crucial driver of economic growth, China has seized the opportunity to cement itself as a leader, thanks in part to robust data collection and government support. India risks missing out on the transformative potential AI holds — beyond just automating tasks, it could drive advances in medical research, logistics, smart cities, and more.

India’s dependence on services might yield a stable revenue stream in the near term, but offers limited protection against global disruptions. When the U.S. or European Union economies slow, Indian firms inevitably feel the pinch. Meanwhile, self-sufficient innovation hubs like China remain resilient, producing homegrown products that can be exported globally, ensuring sustained economic strength.

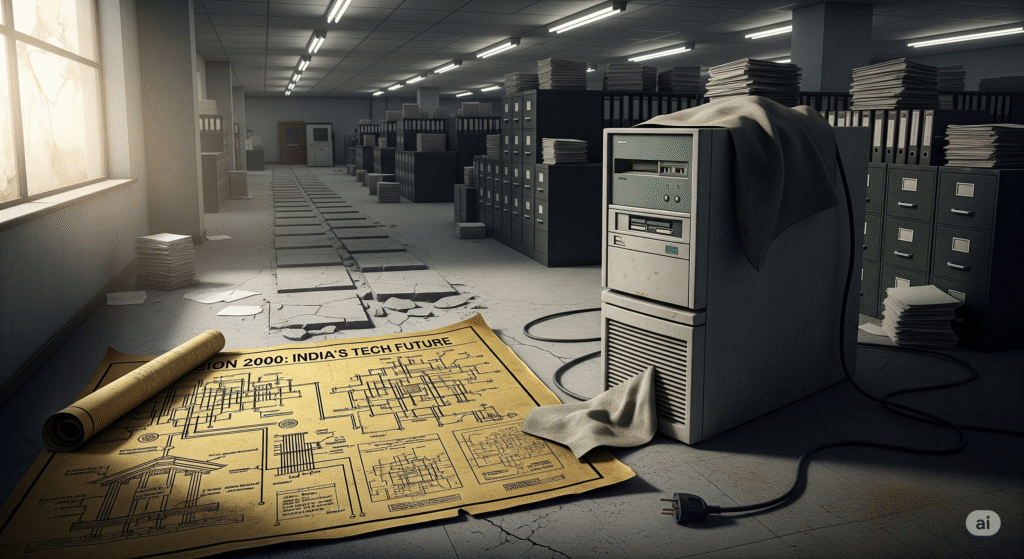

Learning from Past Visionaries

India’s most significant scientific achievements — such as its nuclear program and space exploration initiatives — were largely driven by visionary leaders like Homi Bhabha, Vikram Sarabhai, and A.P.J. Abdul Kalam. They championed a culture of self-reliance, long-term planning, and the pursuit of advanced research.

Today, critics argue that neither the government nor major private-sector players are displaying that same level of forward-thinking ambition. The result is a system that applauds quarterly profits in IT services, but underfunds research in emerging technologies like AI, biotechnology, and new energy systems.

Where Do We Go from Here?

Economic and social commentators suggest a multi-pronged approach to shift India’s trajectory:

- Elevate R&D Investment: Move beyond the current 0.7 percent of GDP on R&D to match or exceed China’s 2.4 percent.

- Reform STEM Education: Update school and college curricula to align with cutting-edge technologies — robotics, AI, and biotechnology — while bolstering vocational training for skilled manufacturing.

- Encourage IP Creation: Offer tax breaks, grants, and other incentives for homegrown startups and established firms to invest heavily in product design and patents, rather than merely providing outsourced services.

- Long-Term Policy Planning: Emulate the strategic thinking behind China’s “Made in China 2025” initiative, with clear targets and timelines to develop domestic ecosystems in critical sectors.

India’s potential is vast. It still boasts one of the youngest populations in the world, a relatively stable democratic government, and a thriving private sector. Yet capitalizing on those advantages demands a willingness to invest in riskier, longer-term ventures — precisely what underpins genuine innovation.

A Tipping Point

As global economic shifts accelerate and technologies like artificial intelligence reshape industries, India stands at a crossroads. Will it continue to take pride in its service role — enjoying steady income but ceding technological leadership to other countries? Or will it muster the same collective will and vision that once propelled its nuclear and space programs, finally charting its own path to becoming a tech-manufacturing powerhouse?

The stakes are higher than ever. If India fails to embrace genuine innovation and advanced manufacturing, it risks missing a once-in-a-generation opportunity to lift hundreds of millions out of poverty and firmly stake its claim as a world leader. In a rapidly evolving global landscape, merely following might no longer be enough.